You can find the original article on the BGG website.

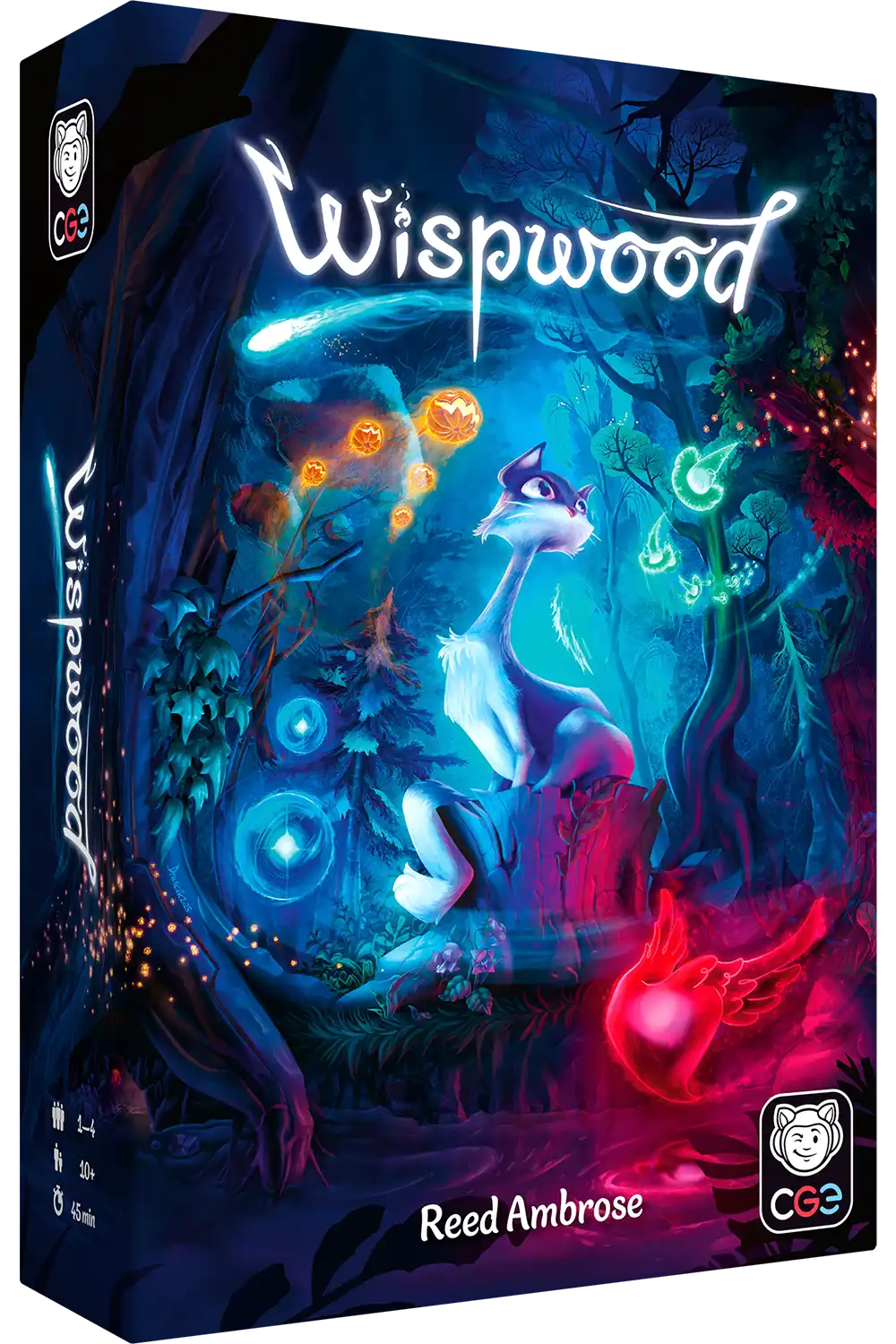

Hello there,Reed Ambrose here, designer of Wispwood, a new tile-laying/polyomino game about magical lights, i.e. wisps, illuminating a forest and luring a cat. Because what cat doesn’t follow a light? Maybe a chonky cat?This game began in early 2020, right before the pandemic hit the US, but it was not the pandemic that held my game back from being published 5 years later. I didn’t need a pandemic to get in the way of my game’s success or development because I can do that all too easily on my own. If you will, allow me to share how I slowly got out of the way, learned some valuable design lessons, and came to publish Wispwood with Czech Games Edition (CGE).

No Polyomino/Tetris-Shaped Pieces?

The game first formed because of an ambitious design goal: I wanted to design a polyomino (i.e. tetris-shaped pieces) game using only 18 cards. You might be wondering how do you make a polyomino game without any polyomino-shaped pieces? That’s a fair question. (You won’t find any in the final production either.)

With those self-imposed limitations, I needed a card to be more than a card. If polyomino shapes are formed with individual blocks, I needed a card to represent one of those blocks within the shape. I also needed the card to tell the player what shape could be formed. Where the design went wrong (because of the 18-card limitation) was when I asked players to imagine the rest of the shape on an imaginary grid. Rather than imagining that, you can see the example card below forming a 1-by-3 shape and then imagine how much you don’t need to play the original 18-card game!

[Example from the 18-card game’s rulebook. The game is named Dreamt. The goal of the game was to just fill in the grid shapes over 3 rounds.]

As a lifelong chess player, I think my “imagine the space” part of my brain kicked in, and a small idea was planted: divide the shape into blocks and have one block be different from the other blocks in the shape. (I’d like to shout out Ryan Laukat and his game, Roam, for being an inspiration.) At this point, I couldn’t see the forest for the trees, but the idea was there.

In Wispwood, the face-up tile is your wisp while the other tiles in the shape are made up of trees (i.e. the backside of all tiles). Every turn, you are placing a wisp and trees into your forest as a polyomino/tetris shape. There is a puzzle contained within each shape you place. Which of the tiles in the shape should be the wisp tile? Where do the tree tiles go because you score for those too? This mechanic is a small puzzle within the larger puzzle of fitting the shapes into your forest to form your grid.

[Example image from the prototype’s rulebook of the same shape with different wisp tile locations in the shape.]

For future reference, let’s call this idea “how shapes are formed” because I will share more about it. This idea stayed the core concept for the game.

Create Your Own Spatial Puzzle

Spatial, tile-laying/polyomino games have a natural progression of filling a space/grid/board. What once was empty is no longer, but that progression of “fill the space” is (usually) the game.

With the new idea of “how shapes are formed,” it allowed me to dream up a new type of progression that differs from just “fill the space” progression. The “fill the space” progression is still in Wispwood within each of its three rounds. Each round, you are building your forest grid with wisp and tree tiles, i.e. a 4x4 grid for the first round, 5x5 for the second, 6x6 for the third. Adding one row and column each round is not that interesting if that’s all you are doing from round to round, but that isn’t all!

There is a second, overarching progression in the game. Let’s call it the “spatial puzzle” progression; it carries over from round-to-round. What if certain individual blocks of the polyomino/tetris shapes remained between rounds? If you recall from the “how shapes are formed” idea, we have an individual block within the shape being different from the rest of the blocks in the shape (i.e. the wisp tile). So, what if between rounds we clear those other blocks, the tree tiles, and keep the wisp tiles where they are? The wisp tiles remain and create fixed tiles for you to fill in around for the next round.

[Example of the first round ending (4x4) left and then after removing the tree tiles on the right. Now, fill a 5x5 grid for the second round! (Prototype art)]

Now, your choices in the current round affect the next round spatially, and you create your own spatial puzzle to solve each round with a slightly bigger grid to fill. And that’s how I shifted all the blame from the designer to the players… ha, just kidding, kind of. I mean, you do create your own puzzle.

Friends for the Win

Despite creating both of those ideas (i.e. how to form a shape and the spatial puzzle progression) with the 18-card version, the problem for me was seeing past the 18 cards.

I revisited the game some in the following years, but still I never thought to break it out of the 18 card format, and so the game stayed on the shelf more days than not in those years. I’d like to briefly pause here and say that this idea of publishing an 18 card game with a mechanical twist was a darling I couldn’t kill for a long time. My desire to publish such a game got in the way of this game becoming a better version of itself sooner. This lesson is not an easy one to learn, and I had to experience it to know otherwise.

Partly in my defense, it didn’t help that two of my good friends are Steven Aramini and Danny Devine, designers of one of, if not the best, spatial 18 card game, Sprawlopolis. I admire their game a lot and aspired to make one myself. So, I had that going for me, too. Also, I’d be remiss to not mention that their paws are all over my games, and my games are much better for it. They are great designers and even better humans.

It wasn’t until another good friend told me in early 2024 that I should really make games that I would enjoy playing like spatial games. As a lifelong chess player, I enjoy most spatial and abstract games, but up until this point I had focused most of my designs on other types of games. The advice struck a chord with me, and I realized I really didn’t design many games that I would love to play, despite designing for more than 7 years at this point. Instead, I would try to design games with a novel idea or unique twist, but they weren’t the kind of game I would choose to play over and over again.

With that thought in mind, I revisited my old designs for games with any semblance of spatial or abstract qualities, and I found my old friend, my 18 card game, again. Finally, I began to think about the game in a new way, beyond the 18 card restriction. Soon after, the cards turned into square cards and then into square tiles. The number 18 was long gone, but much of the core remained.

Fantasy Lights Lure Felines in the Forest

What was a purely abstract 18-card game of filling in grids of increasing size and various shapes didn’t change as much as you might think. It had a good foundation to build upon. The three rounds stayed and so did the increasing sizes of the grid each round. A big difference here was that I simplified them into perfect square grids instead of grids of different shapes.

The two other big changes were theme and score cards. For the theme, a Roman city builder rose and fell before I settled on a favorite literary element of mine. I have long loved the idea of ignis fatuus, the Latin phrase, translated foolish fire, is an umbrella term for all lights leading followers true or astray in a marsh or forest, e.g. will-of-the-wisp. Of all the possible animals, I added a cat because I thought that was silly and fun since cats follow laser lights or flashlights. Why wouldn’t they also want to chase after these lights or wisps? Despite publishers usually changing the theme, the theme was kept!

[Early prototype of square cards with a Roman city builder theme. You can see the polyomino/tetris shapes were on the cards, but were later moved to a central board.]

Prior to designing games at all, I had already built lore around wisps and the different types whirring in the woods, so naturally it felt right for them to take on different personalities in the form of scoring cards. These scoring cards represent the desires of the wisps and give you a glimpse into their unique behaviors. The scoring cards give each wisp type (Witch, Holy, Jack, and Orb) a purpose for its placement: Witch light likes your cat, Holy light likes trees, Jack light dislikes Jack light, and Orb light likes all light types. Don’t forget about the tree tiles! They score too. As obvious as it might seem, scoring cards were honestly the last big thing to be added into the game.

The Need for Speed Pitching

Since 2016, I’ve attended BGG CON every year in the fall. Only in the past couple of years have I started to pitch games at that convention. Suffice it to say, none of this was overnight success for my first published game, and for any designers out there who need to hear this, it’s okay to design in the dark. Since the pandemic, I’ve had a few years of pitching to hone my skills and that was necessary. This past convention included a speed pitching event, which I signed my game up for and got accepted ahead of time. Initially, I did not know the five publishers who would be there, but it was a good group, gathered and organized by Unpub (thank you Ben and team!).

One of the companies there was Czech Games Edition (CGE), not a company I was expecting to pitch this game to because of their catalog. They have games on both ends of the spectrum, from party games to heavy games, but not much in the middle. I was even told at the pitch by CGE that it didn’t fit their catalog, and so I was surprised to get an email a couple weeks after with them asking for the files to print a prototype for their internal testing day. I still didn’t think much of it as I’ve had companies ask for prototypes before with no results, and I knew they had already told me it didn’t fit their catalog, so my expectations were truly low.

It wasn’t until a month or so later when I heard back from them that they were really interested after their company took a staff survey for a potential new game to publish this year. To say I was thrilled is an understatement. We have been working together ever since to develop the game and bring you the best version of it. It’s been a dream working with CGE and their team.

If you ever find yourself playing Wispwood, I hope you allow your mind to wander for a little while in its magical woods with whimsical wisps, following them in the forest as they fill it with light and lure the most curious of cats.

Reed Ambrose

Designer of Wispwood

%20(1).png)